One of the arguments for film being better than digital is that it feels organic. Film is not exact from roll to roll; like snowflakes, each roll is unique. A systematic pattern of pixels will not produce the randomness of halide crystals in an emulsion. People tend to forget that the lenses are what make things inherently different. Using vintage lenses, with all of their flaws and imperfections, can help give your images a more film-like look.

Back in the time before the use of computers, lenses were made by hand and had character to them. They could vary from one to another, especially the off-brand ones. It wasn’t uncommon for a photographer to have a slew of nifty fifties each with its own characteristics. Now, a photographer might have a Canon 50mm f/1.2L and a Sigma 50 f/1.4 Art Lens, but it will be like every other Canon or Sigma; this makes everything convenient, and this makes everything boring.

I love the story about how Stanley Kubrick found his perfect lenses. He would receive a batch of 10 to 15 lenses from Zeiss. After meticulous testing, he would find the best one and send the rest back. Doing this today would result in 10 to 15 almost identical lenses. Camera companies have aimed for perfection in modern lenses so much they have made them uniform and void of character.

[REWIND:3 Canon FD Lenses Mirrorless Shooters Should Consider]

Each one of Kubrick’s lenses behaved like the characters in one of his films; they had imperfections and flaws. To write a perfect character would be boring; they could do no wrong, be incorruptible, and would have no secrets to hide. The audience loves flawed characters, ones that have secrets and imperfections. If lenses were characters helping tell your photographic narrative, would you choose the perfect one or the one that has a bit of character? I have an ensemble of characters, each with their own flaws, which help me better share my photographic story. Here is a list of three and why I choose to use them.

Tou/Five Star 28mm f/2.8 – $10-$30 on eBay

Tou/Five Star lenses never come to mind when you think of quality (they hardly come to mind at all). This little, hidden gem is one of the best 28mm’s I have ever used for video. I specifically use this lens when trying to mimic that cinematic look. Bright sunlight destroys the little contrast the lens has, making the image flat; perfect for color grading. There are severe chromatic aberrations present, which is to be expected from such an inexpensive lens. The five Star doesn’t show the typical purple fringing of other glass, the highlights instead bloom and glow; behaving similarly to the way old celluloid films do. The most interesting aspect is the 1:5 magnification “Macro,” which isn’t huge, but does make for some interesting pictures.

Pentax Super-Takumar 35mm f/3.5 – $72-$94 on KEH

I think of this lens as the humble do-it-all. It can produce sharp, contrasty, three-dimensional like images all in a small package. The all metal construction means this lens can take a beating. Even after having an unfortunate accident with a Dremel trying to remove a broken lens adapter, this lens still performs amicably. The aperture may be as wide as the more modern Sigma’s 35mm f/1.4, but I would choose the color rendition of the Takumar over the Sigma any day.

Canon FL 50mm f/1.8 – $7-$35 on KEH

This is the wild card of the bunch. The lens is not the sharpest lens wide open, and I’ll admit it spends more time on the self than in my camera bag. When it does make it out in the field, the pictures it produces can be hit or miss. Why then do I keep it? Two words: Swirly Bokeh. Old lenses like the Canon have been stored in closets, garages or attics. These are not ideal locations. Humidity and prolonged temperature changes can cause the coatings to wear and degrade. Shooting through partial or missing coatings can cause interesting bokeh or lens flares.

[RELATED: Fotodiox Pro Lens Adapters | Worth The Premium?]

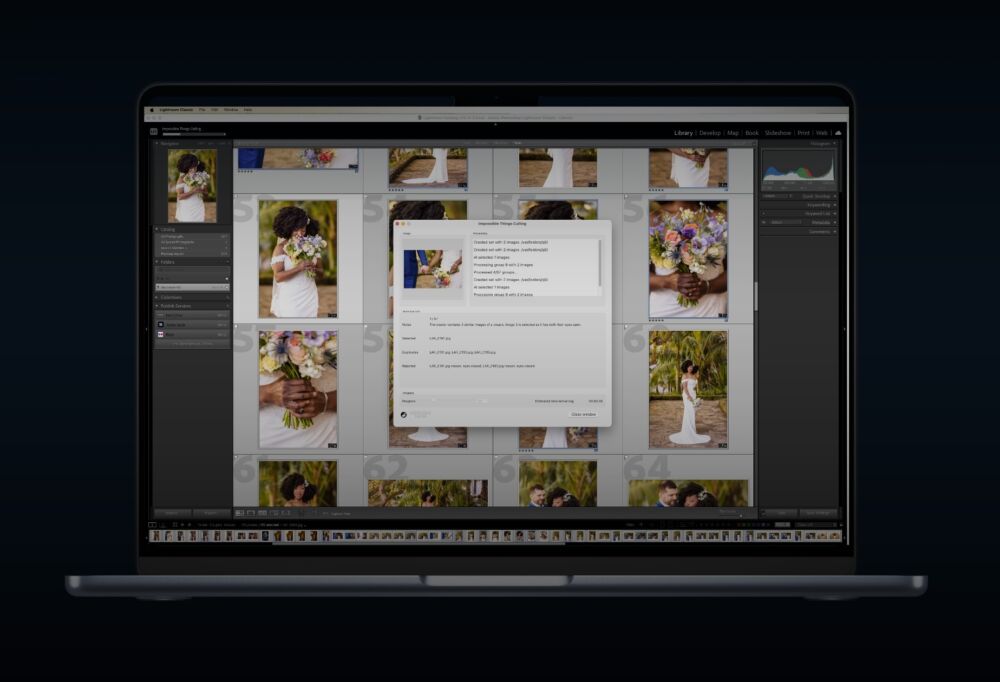

With focus peaking and smaller flange distances, mirrorless cameras like the Sony A7 have made it more convenient (and cost-effective) to use vintage lenses in the digital age without the use of corrective optics. Most photographers would rather create “imperfections” in a controlled environment like Lightroom than experiment with vintage glass; this can help establish an identity or brand. Plugins or recipes can be repeated to give two images the same look, but what can’t be mimicked easily are optical abnormalities in old glass.

The photographic community tends to dwell in facts and figures. DXO marks and MTF charts get tossed around like they are gospel. The tests are done in controlled studios under certain parameters; they will not tell you how a lens will behave in a certain situation. The truth is that the standard 18-55mm kit is inherently better than glass produced 15 to 20 years ago, but it is far from anyone’s go-to lens.

Whatever lens you choose, be it vintage or modern, don’t sit on the facts, number of elements, nor the shortcomings it has over another lens. Go out and shoot with it! The best lenses are always the ones you have with you.