Expanded Explanation of Aperture

In photography, an aperture is the opening of a lens used to control the amount of light necessary to expose the sensor/film; in addition, the aperture is used creatively to control the compositional use of depth of field. A smaller (closed) aperture restricts light and increases the depth of field in a scene, whereas a larger (open) aperture allows for more light and decreases the depth of field within a scene.

APERTURE FOR EXPOSURE CONTROL

Aperture is one of the three pillars within the exposure triangle, shown below.

In our introduction, we simplified the exposure component of Aperture to the following: larger (open) apertures allow more light to reach the sensor/film, while smaller (closed) apertures allow less. The pupil of your eye works in the same way! Your pupils naturally close to restrict light in bright environments and open (dilate) to allow for more light in dark conditions. Hold on to this simple truth as we discuss the details of Aperture.

First, let’s talk about how Aperture is measured and depicted. When we discussed ISO and Shutter Speed, number increments were naturally intuitive. A higher ISO speed represents higher sensor/film sensitivity, and thus more light, but also with the downside of decreased image detail. A higher Shutter Speed represents the shutter opening and closing faster, to freeze motion and also reduce the time for light to expose the sensor.

However, we see Aperture measured in numbers such as “f/2” or “f/2.8.” It’s not exactly intuitive what these numbers mean. This is especially the case when we’re told that raising the aperture number, f/2.8 to f/5.6 for example, is actually decreasing the amount of light.

The reason for this is that Aperture is measured as a fraction, similarly to Shutter Speed. The number, (f/2, 2.8, 4, 5.6…) is the denominator of that fraction. Before we worry about what the “f/” actually means, let us first imagine the “f” being replaced by a 1:

- 1/2 is a bigger number than 1/4

- 1/4 is larger than 1/8

- 1/8 is larger than 1/16, and so forth…

From this, we can see and understand intuitively that as the aperture number (denominator) increases, the amount of light decreases. When we see the f-number displayed as fractions we can then understand that an increasing f-number is, in reality, a smaller number and thus denotes a smaller aperture opening. In fact, I can show you this with the following example. When all other settings are held constant, look at how each of the images below gets darker when the aperture or “f-number” increases.

In the examples above, we are showing “full-stop” increments, meaning each change in the aperture is yielding an image that is 2x (100%) brighter than the last. Thus when a photographer says “increase the exposure by one stop” they mean double the light; conversely “decrease the exposure by one stop” would mean, cut the light in half. If you want to read more about the term “stop” or “f-stop” take a look at this article. For now, let’s keep moving forward.

As we discussed earlier, Shutter Speed and ISO increments naturally make sense. They move in increments that are intuitive: double the number is double the light; half the number is half the light. What throws us off about Aperture is the fact that the numbers don’t intuitively double/halve in the same way.

For example, we know that f/4 is darker than f/2 because f/2 is a larger fractional number. What’s tough to understand is that f/2 is not one stop brighter, it’s actually two stops brighter. Why is this?

Below, you can see a common set of apertures from f/22 to f/2.8 on a classic manual-aperture lens. (Note: most modern lens apertures are controlled electronically by the camera body.)

The reason lies in the fact that a lens aperture is a circular object, which is measured by its diameter. (I will provide a complete explanation down below.) For now, I want you to simply understand that as a fractional measurement f/2 offers twice the total aperture size (area) for light to enter the lens than f/2.8. Thus, the image is 1-stop brighter. f/2 offers four times the aperture size compared to f/4, thus, the image is 2-stops brighter.

I know it’s probably still a bit confusing. Rest easy at this fact, if you’d like to know the calculations, look below. But, if not, it will make absolutely no difference in your creative ability as a photographer.

For now, take a look at this graphic that represents Lens Aperture sizes in 1-stop increments.

Let’s now move on to discussing the creative or compositional use of Aperture in the next section.

APERTURE FOR CREATIVE CONTROL

There are three primary creative uses for Aperture that I want to discuss in this section as follows: Depth of Field, Flare Patterns, and Sharpness.

Depth of Field

The primary creative use of your lens’ aperture is for controlling what is called Depth of Field, or, how much of the image is in focus. To understand how this works, imagine that you have set the focus on your lens to be somewhere in the middle of a scene as shown below.

As you raise the f-number aka “stop down” your lens aperture, both the foreground and the background will begin to come into focus. This is known as increasing the depth of field. As you lower the f-number or “open” the aperture of the lens, the foreground and background fall out of focus. But, how can this control be used creatively? That’s what really matters.

A portrait photographer may often use a wide or open aperture creatively to ensure that a background is out of focus. This brings attention to the subject rather than the background (known as subject isolation) as shown below.

Canon Rebel DSLR, with Canon 50mm f/1.8

Conversely, a landscape photographer will often close or stop down the aperture to ensure everything is in focus, from the nearest subject to the horizon as shown here.

F/16, ISO 100, 2 minute long exposure, 24-70mm @ 24mm, Nikon D750

Put another way: with a fast aperture like f/1.4 or f/2, your lens’ depth of field will be very shallow; your focus will appear “selective”. Whereas at f/11 or f/16, your lens’ focus may include everything from the nearest subject to the distant horizon!

Now let’s move on to discuss how the aperture affects incoming light patterns or “flares.”

Flare Patterns and Sunstar Effects

One characteristic unique to each lens model, despite similar focal lengths, is how the aperture renders flare patterns and starburst effects.

The term “flare” is used to describe any light source directly entering the lens. The look of that flare is largely a factor of the number of blades in an aperture’s design, in addition to a lens’ optical (glass) design. Many modern lenses are designed to minimize flare or render it aesthetically pleasing. Many older lenses have highly unique flare characteristics, although some have innumerable flare “dots” that simply distract from an image. Choosing a lens based on its flare character is usually something reserved for portrait photography and other similar genres in which flare can actually be used as a creative tool, whereas other photographers such as landscape shooters may avoid any type of flare at all costs.

That said, you can also control the look over that flare by opening or closing the aperture. In addition to increasing the depth of field, a closed or small aperture opening will render incoming points of light as “starburst” patterns. The number of points on the star correlates to the number of blades in the aperture design as shown below.

A wide-open aperture will cause flare light to appear more circular and “bloom” around objects within the scene. Blooming is when light appears to wrap around an object as shown below.

A wide-open aperture will cause flare light to appear more circular and “bloom” around objects within the scene. Blooming is when light appears to wrap around an object as shown below.

Canon 5D mk3, Canon 35mm f/1.4 L mk2 | Aperture: f/2

Canon 5D mk3, Canon 35mm f/1.4 L mk2 | Aperture: f/2

The unique look of sunstars, on the other hand, is largely influenced by the number of aperture blades and whether or not they are a rounded blade design. If you are interested in sharp, pointy sunstars, know this: older lenses (Nikon AI-S, Canon FD, Pentax M) tend to create the perfect, sharp-pointed sunstars.

Same focal length & aperture, different sunstar patterns

Nikon 35mm f/1.8 G ED, Nikon 35mm f/2 D

Now that we understand this unique characteristic of lens apertures, let’s move on to discuss a more straightforward aspect of stopping down a lens: sharpness!

Optimal Detail and Sharpness

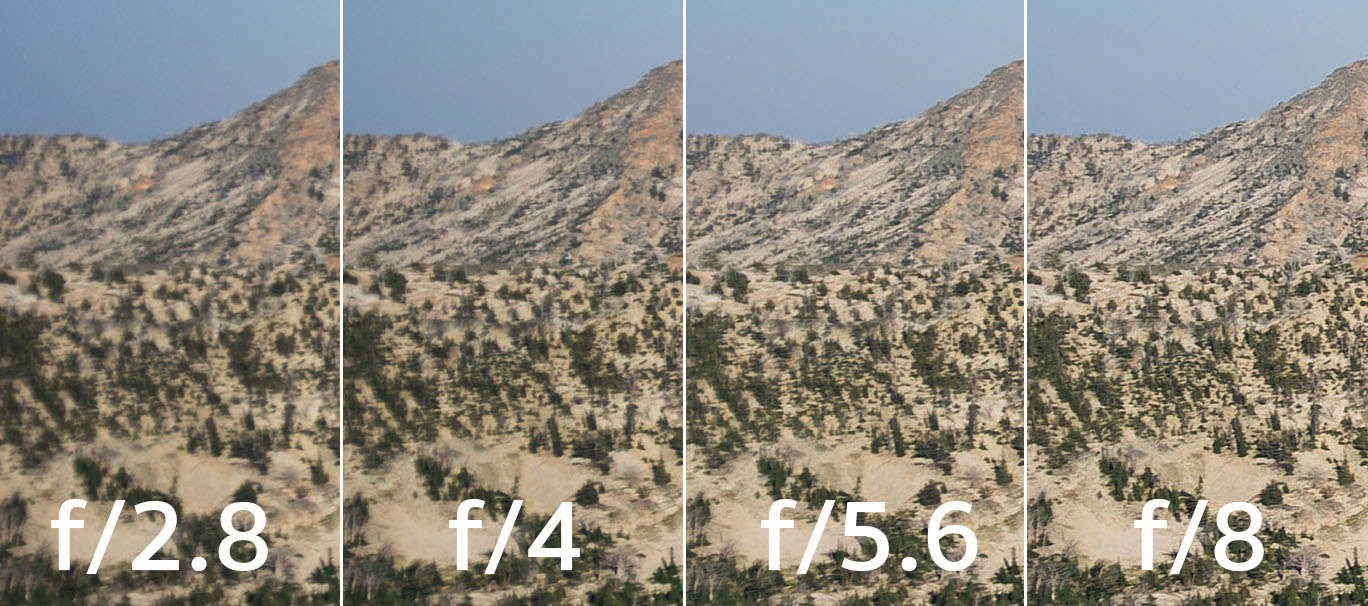

It would be inaccurate to assume that a lens’ aperture affects exposure and depth-of-field only, and that actual sharpness is a separate characteristic of the optics (the glass) in the lens. Actually, aperture also affects the sharpness of an image too. Lenses are inherently less sharp at their fastest, widest apertures, and stopping down the aperture will increase the sharpness of in-focus portions of the image, even in areas that were already within the existing depth of field.

(Click To Enlarge)

As a simple rule, usually, a lens will be at or near its sharpest when stopped down 2-3 stops. For example, an f/1.4 prime lens will become extremely sharp at f/2.8 or f/4. An f/2.8 zoom lens, such as a 70-200mm, will become extremely sharp by f/5.6 or f/8. However, beware of diffraction which we will discuss in the technical details below.

Thanks to modern design technology, most new lenses are very sharp even at their fastest aperture. Creatively, this allows a photographer to choose almost any aperture they wish, without severely compromising image quality.

However, achieving extreme sharpness may not be the right creative choice, in some conditions. Many portrait photographers intentionally use a lens at its widest, fastest aperture, because the slight softness is actually flattering on faces and skin. For this reason, prime lens apertures such as f/1.2, f/1.4, and f/1.8 are very popular choices.

This is a subjective creative decision, of course. Shooting portraits at any aperture can yield artistic results, and every artist will experiment with different techniques to see what fits their own unique style.

SUMMARY

Each camera setting plays an important role in the exposure triangle, and also has a unique creative purpose that can help you achieve your creative vision. Adjusting your aperture, like Shutter Speed and ISO, has various benefits and drawbacks that you can use to your advantage in any situation.

See the chart below for a quick summar of the exposure triangle:

COMMON APERTURE TERMS/JARGON

Even after you understand the numbers, just talking about aperture can seem confusing, because there are so many different terms that photographers use. So, here is a quick, categorized list of the two “directions” you can dial your aperture:

Opening to a BRIGHT exposure with your aperture may be referred to as:

- “Fast”

- “Wide”

- “Big”

- “Low” Number (avoid this term; too confusing!)

- “Shallow”

- “Bright”

Closing to a DARK exposure with your aperture may be referred to as:

- “Slow”

- “Narrow”

- “Tight”

- “Small”

- “High” Number (avoid this term; too confusing!)

- “Dark”

Related Articles to Aperture Definition

Natural Light Portrait Tips | Use Hard Light to Shape the Body

Fall Children’s Portrait Photography Tutorial

Learn How to Photograph Lightning with These 7 Essential Tips

ISO, Aperture & Shutter Speed | A Cheat Sheet For Beginners

5 Tips on Shooting Sharp Images with a Wide-Open Aperture

6 Must-Have Lenses For Wedding Photography

5 Milk Bath Boudoir Photography Tips

Macro Flower Photography Tips

How to Become a Sports Photographer

How to Get Correct Exposures Without a Light Meter

Creative Photography Ideas | How to Shoot “Water Hats” on the Cheap!